What does it mean to own an artifact? The recent sales of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are not only an art phenomena, they also are an ownership phenomena. Here is digital art by Beeple entitled Bull Run.

This is an edition of 271, and someones who owns one of the NFTs is probably willing to sell it to you. But, you may ask, what are you buying? The artwork is digital, and you can, if you like, pin the image and view it whenever you like. That is, you can possess the digital artifact for free. If you buy the token, you will own just the token. And what is the token? It is essentially a file that has been placed on the ethereum blockchain; the file has a pointer to the digital artifact, the image above.

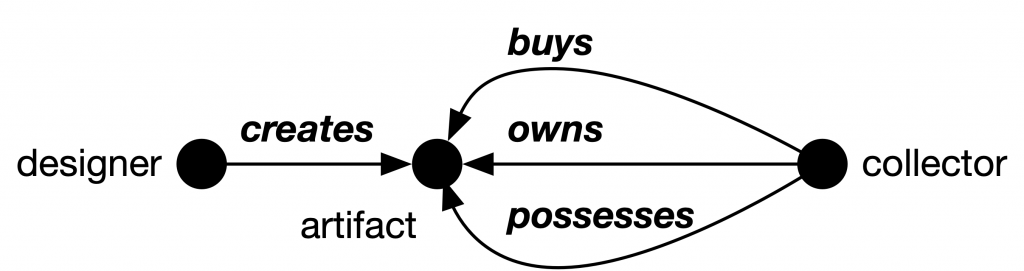

This may seem arcane, but the underlying concept of non-fungible tokens has broad applicability. Consider the sale of a traditional designed artifact:

The designer/artist created some artifact, like a painting, and the collector buys it. The collector then owns it, and possesses it exclusively. The collector can decide to sell it to someone else who will then own it. Or the collector may decide to gaze upon the artifact while sipping whiskey in a hidden windowless room, taking pleasure in limiting access.

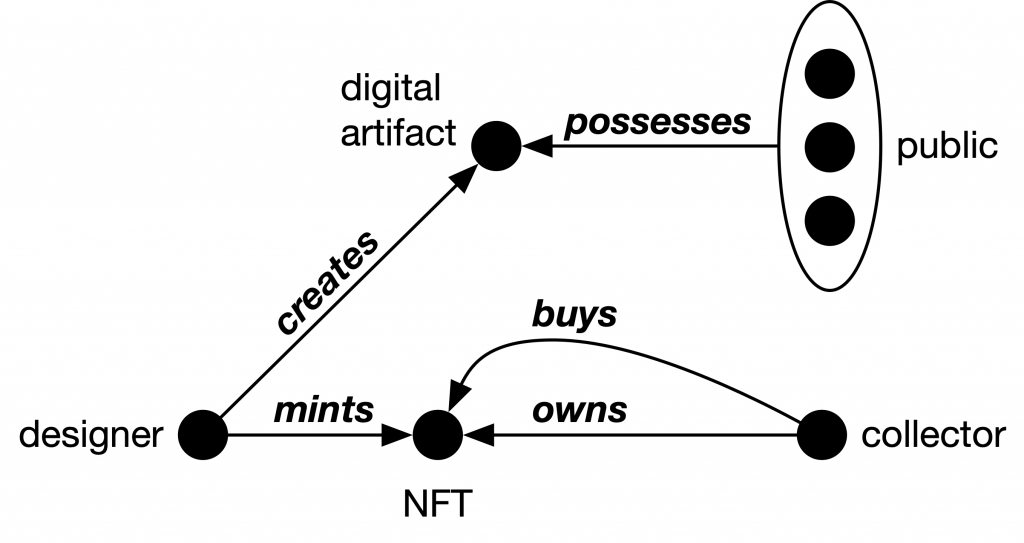

Non-fungible tokens can be used to create different ownership scenarios. Such tokens are like speech acts: they declare ownership. Furthermore, they prove ownership through their cryptographic features. They also can be used to entirely separate the intermixed concepts of ownership and possession:

The designer creates an artifact, in this case a digital artifact like Bull Run. One of the features of a digital artifact is that it can be copied exactly, and so the artifact is set free: anyone is allowed to copy it, print it, put it on a wall, or import it into a virtual world. The public possesses the artifact, non-exclusively. The designer at the same time mints an NFT. The collector buys the NFT, and as a result owns the NFT. The collector can possess the digital artifact, but only in the same way as the public does. There is no exclusivity with respect to the artifact, but there is exclusivity with respect to the NFT.

The purchase is a form of patronage, which may help encourage more production, and may also add to the reputation of the collector. Many tokens also have another feature: if the collector sells the art work to another collector, the other collector pays a royalty back to the artist. This can happen because an NFT can be configured to function as a contract, with computational logic that enforces the transfer of value back to the minter upon every transaction. So everyone in the chain of ownership helps the artist. By contrast, the typical secondary sale of art does not pay royalties back to the original artist.

Ownership and value flows can be designed. They become another tool in the arsenal of a designer. At one extreme, the digital artifact becomes open source, so that everyone can copy it and possess it. This is good for viewership, and popularity overall. The popularity may enhance the value of the NFT, which is targeted toward collectors.

Beeple sold his collage Everydays: The first 5000 days, for $69,346,250. At the time of writing, #224 of Bull Run, which is one of the component images of the collage, appears on OpenSea, and can be purchased from its current owner for 69 Ethereum, or about $143,000. It may be that the more exposure the Beeple digital artifacts get, the higher the value of the NFTs, a kind of preferential attachment.

It is possible we will see all sorts of variations on ownership and possession, because designers can now include ownership as part of the design space. For example, a designer could create a piece based on procedural generation that runs differently according to a random seed. Everyone sees something different, but the NFT owner’s version could be parameterized according to a special seed created by the artist. The artwork doesn’t have to be static, because the NFT can include logic that can affect the digital artifact it points to. In that way, the artifact can change algorithmically with each sale. The design space is large, in that the designer can create digital artifacts that have logic, and also mint NFTs that also have complementary logic. So fluid ownership and fluid possession become aspects of an overall design.

There is another level. NFTs can interact with each other. Indeed, there are now games based on NFTs. Imagine the NFT as the genome of a game character, and imagine that genomes can be modified and recombined to create new genomes that are more fit for gameplay. Each NFT has ancestors. To the extent the character survives in the game, the character is valuable. And the NFTs can potentially be bought and sold. The buying and selling could, for example, transfer value to the characters’ ancestors. That is, just as users of patents may pay royalties, these kinds of trees can create royalty streams for players in the game. How about control? One can imagine the game and the control of the game being distributed to those who play, perhaps according to the degree their contributions get used by other players. These ideas are developed in the game Axie. Related ideas can be seen in descriptions of remix networks and contest webs.